Under the EU’s Growth and Stability Pact, all Eurozone countries are required to bring their deficits below 3% of GDP and to work towards reducing debt down to 60% of GDP, and any country failing to do so is subject to strict deficit reduction targets under the corrective arm of the Excessive Deficit Procedure. Certainly, widespread acknowledgement of the self-defeating Catch-22 whereby austerity lowers growth and thereby weighs further on public finances has encouraged the EU authorities to allow leniency in a number of instances, but this is only part of the explanation. The political and social crises that years of fiscal adjustment have unleashed across Europe have contributed to a wave of anti-EU populism and unprecedented electoral gains for far-right parties in some countries, and the emergence of anti-austerity far-left parties in others. The EU is therefore not in a position to rock the boat any further, as the potential political costs of taking an inflexible stance on debt and deficit reduction measures are now too high in many cases.

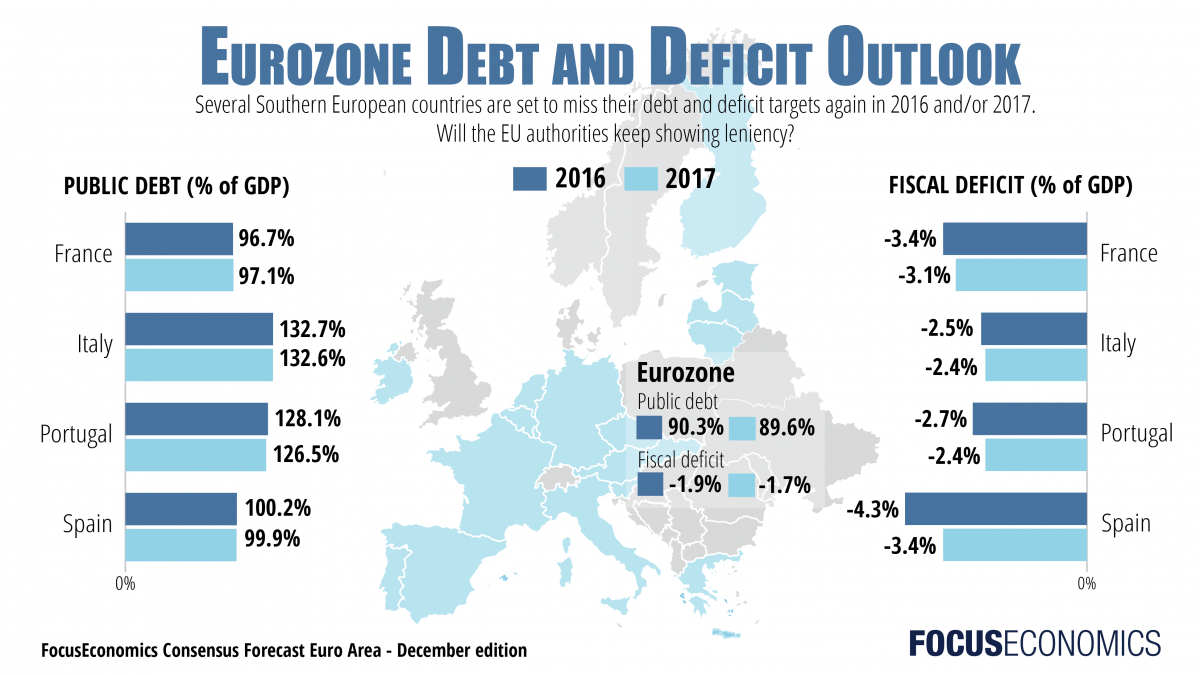

In what follows, we examine the outlook for France, Italy, Portugal and Spain, and the political and economic obstacles that are set to see them breach their debt and deficit reduction targets again in 2016 and/or 2017.

Click on the image to open a full-size version

FRANCE

Debt levels: France’s public debt has reached almost 97% of GDP—the seventh highest in the Eurozone.

Deficit targets: Last year, the European Commission gave France an extra two years again, this time until 2017, to bring its deficit below 3% of GDP. To achieve this, the French government targets a deficit of 3.3% of GDP in 2016 and 2.7% in 2017.

Our Consensus Forecast: France’s budget deficit will come in at 3.4% of GDP in 2016 and 3.1% of GDP in 2017, according to average estimates we produced after polling 34 leading macroeconomic analysts on the French economy. This means that France will not only overshoot by far its government’s own targets, but it will also fail to meet the EU’s requirement by 2017. French public debt is seen increasing slightly from an estimated 96.7% of GDP at the end of 2016 to 97.1% of GDP by the end of 2017.

France’s problem: The French economy has long suffered from a lack of competitiveness and is stuck on a weak growth trajectory, which prevents it from meaningfully reducing its debt and deficit levels. Like its Eurozone neighbors to the South, it is also completely failing to reduce its structural deficit—the part of the overall deficit which is adjusted to exclude the impact of temporary measures and cyclical variations. The economy recovered in Q3 this year from an unexpected contraction in Q2, but growth still disappointed and forced the government to finally admit that its 1.5% growth target for this year looked overly ambitious, long after our analysts had downgraded their outlook. Our Consensus Forecast sees French GDP growing a mere 1.3% in 2016 and 1.2% in 2017—forecasts which have been gradually revised downwards throughout this year from 1.5% and 1.6% respectively back in January.

Beleaguered Socialist President François Hollande has come under attack this year by France’s independent fiscal watchdog, which foresees a high risk that spending will be more than planned—especially ahead of the 2017 presidential elections—and revenues less than expected this year and next. This, in turn, puts France at risk of ever greater fiscal incompliance. Hollande, whose approval rating in France has fallen as low as 4% at times this year, has seriously struggled to make progress with structural reforms. Those that he has pushed through—such as the labor reform approved in July—have invariably ended up being rather a damp squib after intense political and social opposition forced him to water down initial proposals.

With the French left in the doldrums, right-wing sentiment has surged, though arguably more on account of the anti-Islam rhetoric of the French right in the wake of terrorist attacks than support for a right-wing economic reform agenda. Opinion polls suggest far-right populist Front National leader Le Pen is set to face the conservative candidate François Fillon in the second-round run-off of the presidential elections next May, following Fillon’s emergence as surprise winner of the Republican party nominations. Fillon is currently expected to win, and is much more likely than the Socialist Party to be able to attract voters away from Le Pen with his anti-immigrant and socially conservative rhetoric. Happy to be branded a “Thatcherite”, he is promising radical structural reform in France and has announced his commitment to take on the infamous French trade unions, though whether this would prove viable in practice is entirely another question—thwarted reform attempts during his previous life as prime minister when Nicolas Sarkozy was president might suggest otherwise. Moreover, his detractors point out that his headline plans to reduce France’s debt and deficit by slashing government spending and axing public sector jobs are not accompanied by any concrete supply-side proposals to boost French competitiveness and innovation and create jobs.

ITALY

Debt levels: Italy has the second highest level of public debt in the Eurozone after Greece, at approximately 132% of GDP—broadly the same level that Greece had at the outset of the crisis in 2009.

Deficit targets: In May this year, the European Commission granted Italy particularly generous leeway over its 2016 budget but warned in return that it must tighten its fiscal policy next year. It set a 2017 budget deficit target for Italy of 1.7%, arguing that this this target—which is lower than the goal for several other Eurozone countries—is necessary in order to reduce the country’s huge debt pile.

Our Consensus Forecast: After polling 33 leading economists on Italy this month, we see the country’s budget deficit declining only slightly to 2.4% of GDP in 2017, after an estimated 2.5% in 2016. This means that Italy will overshoot by far the 2017 target set by the Commission. Italian public debt is forecast to remain broadly stable at 132.7% of GDP in 2016 and 132.6% in 2017.

Italy’s problem: Italy is failing to reduce its heavy debt burden and the structural part of its overall deficit has been rising since 2014, rather than falling by the 0.5% of GDP each year that the EU authorities ostensibly require until a country balances its books in structural terms. Italy has attributed its poor deficit performance this year to extraordinary spending on migration and post-earthquake reconstruction, though other ongoing structural features such as a weak banking sector and poorer-than-expected growth have also contributed, with our Consensus Forecast putting GDP growth at only 0.8% both this year and next. Ultra-low inflation has also hindered Italy’s debt reduction efforts.

The European Commission could potentially reject Italy’s 2017 budget proposal, under which the country is set to infringe its debt and deficit targets by a long way next year, but no decision is expected before the constitutional referendum called by Prime Minister Matteo Renzi on 4 December. The proposed constitutional reform would reduce the power of the Senate (upper house) in order to make parliamentary decision-making more efficient, but Renzi has also repeatedly made his political future conditional on a win for the “Yes” vote, stating that he will resign if he is defeated—a strong possibility. A number of analysts are skeptical as to whether Renzi would actually resign, but if he does, any new prime minister, though likely to be supported by a similar parliamentary majority, would be focused mainly on carrying the country over to the next elections due to be held by May 2018. This risks further delays in implementing structural reforms, which have already been paralyzed for months since Renzi has sought to avoid negative consequences for the referendum vote.

Both Renzi’s future and Italy’s debt sustainability are also on the line due to the risk of an imminent collapse of the country’s third-largest bank, Monte dei Paschi di Siena. As we anticipated, investors are reluctant to throw more money into an institution that has already been bailed out several times previously to no avail, and the bank is rapidly running out of time to meet a year-end deadline to raise an extra EUR 5 billion of capital—five times its current market value—and offload scores of NPLs.

PORTUGAL

Debt levels: Portugal has the third highest level of public debt in the Eurozone after Greece and Italy (in that order), at not far off 130% of GDP—broadly the same level that Greece had at the outset of the crisis in 2009.

Deficit targets: In August this year, the European Commission decided to waive a budgetary fine on Portugal for missing its deficit target last year, at the same time as it did so for Spain, and in Portugal’s case it gave it an extra year, until 2016, to bring its deficit down to 2.5%. Last year, Portugal had missed its 2.5% deficit target by far, coming in at 4.4% instead, mainly since it had to rescue its failed lender Banif.

Our Consensus Forecast: Portugal is expected to miss its 2.5% deficit target again this year with a projected deficit of 2.7% of GDP, according to the average forecast of a panel of 19 local and international macroeconomists that we surveyed on the Portuguese economy this month. Next year, in 2017, our analysts see Portugal’s deficit finally reducing to 2.4%. Portuguese public debt is seen decreasing slightly from an estimated 128.1% at the end of 2016 to 126.5% at the end of 2017.

Portugal’s problem: Portugal’s slow economic growth is hindering its debt and deficit reduction efforts. The Portuguese government is basing its deficit reduction projections on the assumption that the Portuguese economy will grow 1.2% in 2016 and 1.5% in 2017, but these forecasts are far more optimistic than our Consensus Forecast for growth of 1.0% in 2016 and 1.2% in 2017. Weaker-than-expected growth therefore looks set to prevent Portugal from meeting its deficit target this year, and any further downgrades to the Consensus Forecast for near-term GDP growth going forward could even put Portugal’s ability to achieve the 2.5% deficit in 2017 in jeopardy too.

Portugal was praised by the European Commission for its austerity efforts under its three-year bailout program in 2011-2014, during which time the country was led by a center-right government, but the political landscape has since changed. A new Socialist government took office in late 2015 which only has a minority of seats in parliament and is therefore dependent on the support of three far left parties. Socialist Prime Minister António Costa may have somewhat softened his attack on his predecessor’s austerity measures since taking office, but the need to agree policies with radical left parties complicates any reform agenda.

SPAIN

Debt levels: Spain’s public debt remains stubbornly high at around 100% of GDP—the fifth highest level in the Eurozone.

Deficit targets: After deciding in August to waive a budgetary fine on Spain for missing its deficit target in 2015, the European Commission set a new series of targets from 2016 to 2018 in order to finally bring Spain’s overall deficit below the long-targeted 3% of GDP that year. In 2016 it now expects Spain to meet an overall deficit target of 4.6% of GDP, followed by 3.1% in 2017 and 2.2% in 2018.

Our Consensus Forecast: On average, the 33 macroeconomic analysts that we surveyed on the Spanish economy this month expect the country to meet its revised deficit target reasonably comfortably this year, with the Consensus for a deficit of 4.3% of GDP. In 2017, however, our panel sees Spain breaching its targets again, with an average deficit forecast of 3.4%. In both years, Spain is forecast to have the largest deficit of all Eurozone countries, while Spanish public debt is seen at 100.2% of GDP in 2016 and 99.9% in 2017.

Spain’s problem: The resilience of Spain’s GDP growth in recent quarters—the country is growing at one of the fastest rates among EU countries—is key to its deficit reduction efforts. However, the country’s persistent structural deficit (the part of the overall deficit which is adjusted for temporary measures and cyclical variations) still renders its economy particularly vulnerable to future changes in economic climate and puts the country on a collision path with Brussels over the required fiscal consolidation trajectory.

Both Spain’s Independent Authority for Fiscal Responsibility (Airef) and the European Commission have warned that Spain is relying too heavily on GDP growth to reduce its deficit while neglecting much-needed progress with structural reforms to reduce its sizeable structural deficit. Achieving this will depend on whether the new minority conservative government led by returning conservative Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy is able to secure sufficient support from other parties in parliament to push through a reform agenda. The weak government was finally formed in November after two inconclusive elections and ten months of a caretaker government, but it faces an exceedingly tough challenge ahead to successfully build alliances to govern effectively.

Author: Caroline Gray, Senior Economics Editor

Sample Report

5-year economic forecasts on 30+ economic indicators for 127 countries & 33 commodities.