On the economic front, this is to be achieved through two key policies. Externally, the Belt and Road initiative (BRI) is using Chinese capital and knowhow to drive infrastructure development overseas. Domestically, Made in China 2025 (CM2025) seeks to transform the manufacturing sector, moving up the value chain and nurturing world-beating firms in emerging sectors to avoid the fabled middle-income trap.

Both schemes could transform the global economic structure, and Beijing has repeatedly moved to assure other countries that they stand to benefit.

But not everyone is convinced. While the BRI has seen a surge in investment to developing economies and created tens of thousands of jobs, unease is building over onerous debt burdens, leading many countries to scale back their engagement. And CM2025 has stoked fears that the Asian giant will become a direct economic competitor to the West, which is at the heart of the ongoing trade conflict with the U.S.

Faced with rising pushback, the Chinese government has shifted its stance: It is taking a more rigorous approach to BRI projects; has dialed down mentions of CM2025; and is locked in talks with the U.S. regarding contentious areas such as forced technology transfers and creating a level playing field for Western firms in China. Whether or not these initiatives succeed will have a key bearing on the global economy in the decades to come.

A two-pronged approach

The BRI was initially conceived in 2013 as a way of linking China to Central Asia in a throwback to the ancient Silk Road, but its scope has since been radically extended. Today, the project is highly heterogenous and toweringly ambitious, comprising countries representing around two-thirds of the world’s population and over one-third of global GDP. It is focused largely on the developing world, but not exclusively. In late March, for example, China scored a major diplomatic coup by signing up G7 member Italy—to the ire of the U.S.

Against the backdrop of a global infrastructure gap estimated at USD 15 trillion, the BRI focuses on building critical structures such as ports, roads, bridges and railways. Over USD 200 billion has been invested to date—often in countries shunned by traditional lenders—with over 200,000 jobs created in the process. Total investment over the lifetime of the scheme could top USD 1 trillion, according to some estimates.

Analysts at Nomura see a symbiotic relationship: “It helps China address manufacturing overcapacity issues and increase exports. For BRI countries, “Increases in investment, trade, tourism and integration are expected”, they added.

Joanna Konings, an economist at ING, focuses on the potential impact on trade: “The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is increasing transport connections between Asia and Europe. […] A halving in trade costs between countries involved in the BRI could increase world trade by 12%.”

While the BRI focuses on enhancing economic cooperation with the rest of the world, CM2025 is the government’s blueprint to transform the domestic economy. Directly inspired by Germany’s Industrie 4.0 proposals, CM2025 is an aggressive response to concerns over a shrinking workforce, environmental degradation and rising domestic wages, which raise the specter of a pincer movement.

“China is at risk of being squeezed from two sides – the low cost countries, where production of consumer products, like consumer electronics, increasingly reside, and the developed ones, where higher value added products should return thanks to the fourth industrial revolution”, argue economists at Euromonitor.

The government aims to establish Chinese technological leadership in 10 key sectors, including AI, robotics, new energy vehicles and aerospace. Ambitious targets are set for domestic production of key industrial components which are currently imported, such as semiconductors.

China’s ongoing reliance on foreign technology has been brought into sharp relief by the trade dispute with the U.S. In 2018, the Trump administration forced American chip manufacturers to stop supplying Chinese firm ZTE; smartphone production at ZTE promptly ground to a halt.

Beijing is putting its money where its mouth is. A report from the EU Chamber of Commerce speaks of “hundreds of billions of euros of funding in the form of subsidies, funds and other channels of support”.

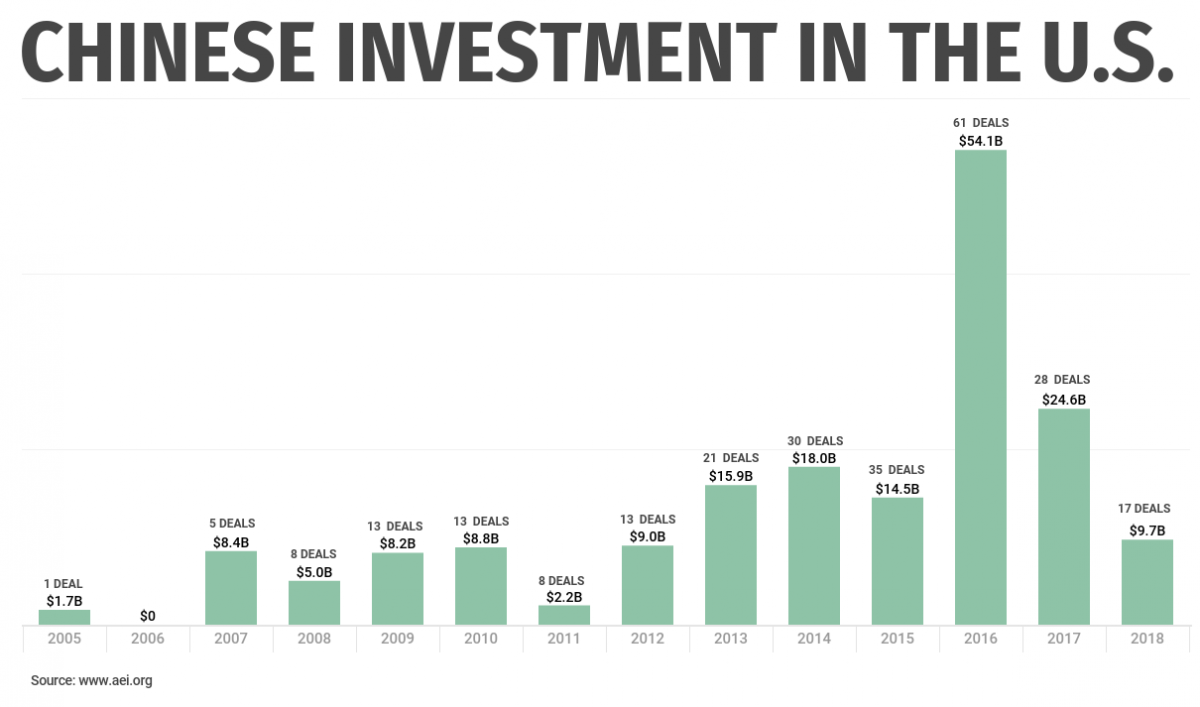

A significant chunk of this capital is being ploughed into an unprecedented acquisition spree, with Chinese firms hoovering up foreign rivals in an effort to gain technological nous. According to data from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, China’s outbound investment in the semiconductor industry soared from less than USD 1 billion before CM2025 was announced to USD 35 billion by 2015.

Click on image to enlarge

Considered jointly, the BRI and CM2025 suggest a significant realignment of the global economy. They envisage a world with the Asian giant at its heart, developing cutting-edge technology in-house which is then exported using Chinese-funded infrastructure to the rest of the globe.

Chinese whispers

However, success is by no means a forgone conclusion, and the economic upshot may not be wholly positive—even for China itself.

Most of the potential trade benefits from the BRI have yet to be felt. As Konings says: “the majority of projects identified with the BRI so far are still in their construction phases […] Trade facilitation may improve as BRI projects are completed, but this may be piecemeal. Significant progress may have to wait for co-ordinated action along whole trade routes.”

Moreover, concerns over the cost of BRI for recipient countries—many of which already have fragile fiscal positions—and the associated accumulation of debt could scupper potential projects before they hatch. In 2019, Malaysia’s new government threatened to scrap a USD 20 billion BRI rail project due to cost concerns, finally agreeing on a much slimmed-down version of the scheme. Myanmar and Pakistan have also scaled back their BRI commitments, while Sierra Leone recently ditched Chinese-backed plans to build a gleaming new airport after warnings from the IMF and the World Bank.

Some countries have already been forced to renegotiate their loans. Ethiopia is the latest example; after being a major beneficiary of Chinese finance over the last decade, in March the government announced it aimed to restructure borrowings related to a railway linking the capital to neighboring Djibouti, amid “serious stress” on repayment capability.

“Markets such as Pakistan and Sri Lanka are already heavily indebted and being involved in the BRI strains their public finances. Sri Lanka, especially, had to hand over its strategic port of Hambantota to China as it was struggling to pay its debt to Chinese companies,” comments Mahamoud Islam, senior Asia economist at Euler Hermes.

Cries in some quarters of “debt-trap diplomacy” may be overblown; aside from the notable exception of Sri Lanka, China has repeatedly shown flexibility over loan repayments. But a failure to address legitimate worries could still sink the scheme, and elevated public debt levels in developing countries could have an economically corrosive effect, by reducing cash available for investment in growth-enhancing areas.

Moreover, substantial writedowns on loans could hurt profitability at the Chinese financial institutions which bankroll the BRI, such as the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China. And enhancing infrastructure in developing countries could allow foreign firms to compete on a more even keel with their Chinese counterparts, hitting the Asian giant’s already embattled manufacturing sector.

Made in China 2025 has caused even greater alarm—particularly in the U.S. and EU, who’s firms tend to dominate the industries in which China seeks to establish global leadership—and the economic impact is far murkier.

Following a surge in acquisitions by Chinese firms, in 2018 Donald Trump beefed up CFIUS—the committee charged with overseeing FDI—amid concerns the U.S’ technological edge was being blunted. Disputes over intellectual property rights and forced technology transfers are at the crux of ongoing trade talks between the two nations.

The EU, which had until recently adopted a more emollient approach, has ratcheted up the rhetoric; a European Commission paper from March this year describes China as a “systemic rival” and an “economic competitor”.

While CM2025 offers benefits in the form of potentially innovative new goods and services, developed nations’ external sectors could be hit. As the EU Chamber of Commerce says, “in the long term CM2025 amounts, in large part, to an import substitution plan. Market access for European business can therefore be expected to shrink.”

With Chinese firms giddy on state subsidies, and answering to government diktats rather than conventional market forces, overcapacity is another concern, with the excess dumped onto global markets—as has already happened with steel and solar panels. This could stifle R&D efforts and leave foreign competitors floundering.

Within China itself, the metamorphosis of the industrial sector won’t be painless. “Disposal of low value-added operations, like consumer electronics assembly, might be hurtful for the economy, where a significant part of the population is employed”, argue economists at Euromonitor.

Moreover, the danger of such a top-down industrial strategy—in stark contrast to Germany’s Industrie 4.0, which seeks to encourage collaboration with local stakeholders—is that huge sums of public money are ploughed into a blind alley, creating products for which there is no discernible market demand.

A second wind

Faced with rising criticism of both of its signature policies, China has changed tack. BRI financing has been reigned in, and the authorities are moving to boost governance standards and auditing mechanisms. The focus of the BRI is also shifting, towards collaboration and joint projects. Third-party agreements have been inked with countries such as France, Spain and Australia, which will see them club together with China to carry out projects.

Mahamoud Islam highlights the importance of this change in approach: “China cannot finance BRI alone considering its domestic financial situation (total non-financial sector debt estimated at 253% GDP) and the amounts at stake. […] In that context, partnership with countries willing to finance the project and private capital will probably be needed.”

The direction of travel; towards a lower-key, more selective and higher-quality scheme. And for all its recent travails, the BRI still boasts impressive pulling power. A summit in April attracted dozens of world leaders and high-ranking officials.

Concerning CM2025, China has also switched to a softly-softly strategy—in an attempt to keep the initiative off the public radar. Unlike in previous years, Premier Li Keqiang did not mention the project once at his annual address at the 2019 National People’s Congress.

There have been some changes of substance too. Following talks with the EU, China recently signaled its willingness to negotiate over forced technology transfers and discuss new rules on industrial subsidies. Talks with the U.S. could yield similar concessions.

Nevertheless, Chinese leaders will not renounce their end goal of achieving economic leadership in emerging industrial sectors. If anything, the trade conflict with the U.S. will only have strengthened their resolve, by laying bare the importance of technological self-sufficiency.

Through the BRI and CM2025, China aims to assert itself at the forefront of the global economy. In doing so, China’s leadership is marking a decisive break from Deng’s prescriptions of a greater role for market forces in the economy, and an unassuming foreign policy. That said, one of Deng’s maxims is still just as relevant to today’s crop of leaders, and runs right through both policy initiatives: “to get rich is glorious”.

Sample Report

5-year economic forecasts on 30+ economic indicators for more than 130 countries & 30 commodities.