The new train link made the headlines for many reasons. Spanning 470km, it slashed journey times from 12 hours on the dilapidated colonial-era railway to under 5, promising to have a transformative effect on the mobility of freight and people. It marked the largest infrastructure development since Kenya’s independence in 1963, and the first major railway project in the country for more than a century. Crucially, it was also almost entirely financed by China, as the first stage of a much more ambitious scheme conceived under the Belt and Road Initiative, which would see a web of similar lines knitting together neighboring Ethiopia, South Sudan, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

Just over a year on, the Nairobi-Mombasa railway has become emblematic of China’s expanding reach in Africa, where the Asian giant has gone from bit player to center stage in little over a decade. As with all Chinese engagement on the continent, the train line offers ample ammunition for supporters and critics alike.

For some, the project is a shining example of the distinct, pragmatic nature of Sino-African relations; a practical infrastructure development addressing a concrete need for better transport links, finished ahead of schedule and employing local workers. The senior Chinese official who attended the opening ceremony described the railway as an “exemplary project of China-Africa cooperation on the construction of roads, railways, aviation networks and industrialization”.

Others are less overwhelmed. The railway reportedly lost USD 100 million in its first year of service. Freight transported on the new line has disappointed, weighed down by loading and customs delays. And, at roughly 5% of Kenya’s GDP, economists have criticized the railway’s elevated cost and warned of rising public and external debt—a concern which dogs Chinese investment in scores of other African countries. Some observers have even gone so far as to describe this type of “debt-trap diplomacy” as a new form of colonialism.

Closer Ties

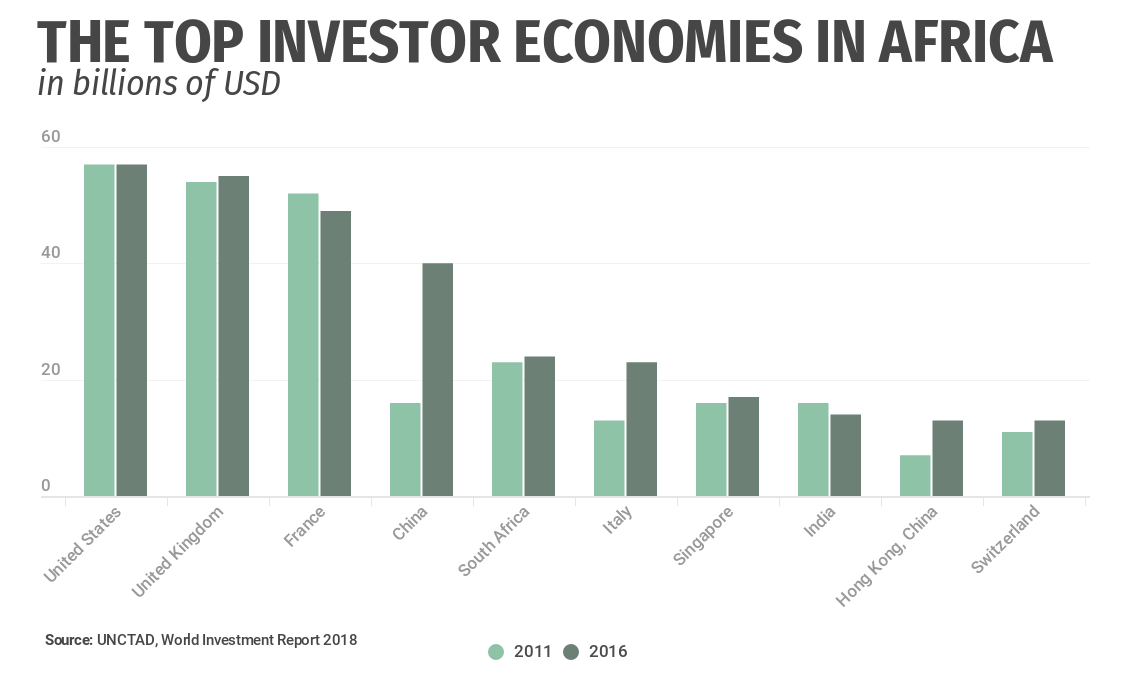

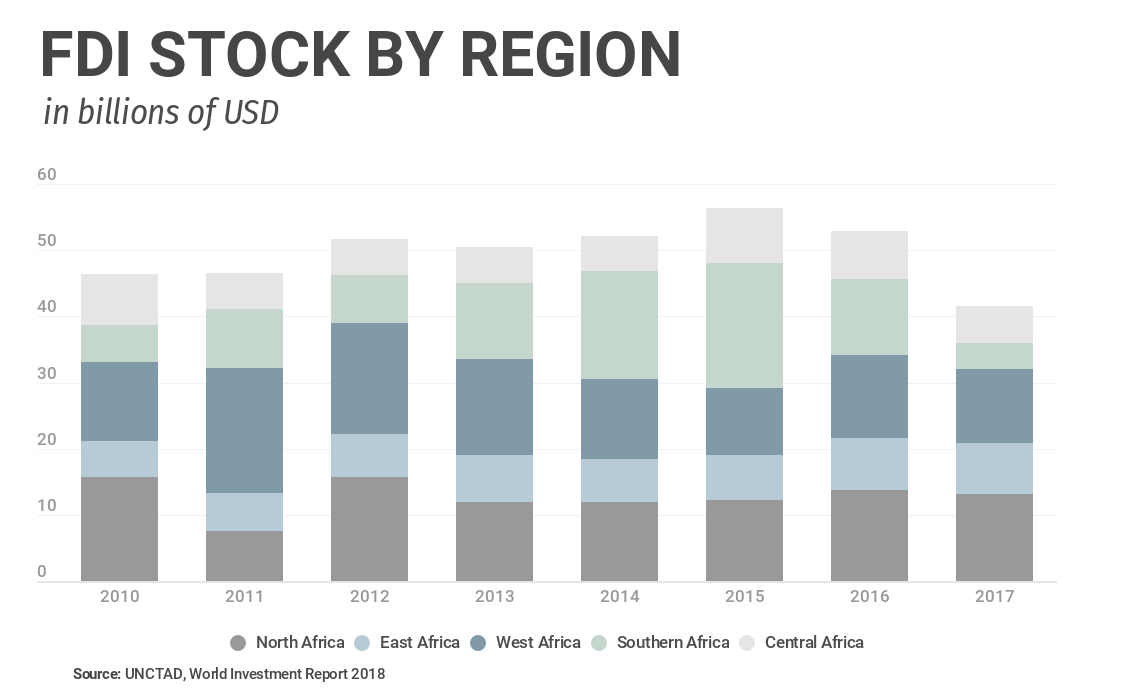

Given the politically charged nature of China’s relationship with Africa, it is vital to separate the hyperbole from reality. According to UNCTAD (United Nations) data for 2016, China had the fourth largest stock of FDI in Africa at USD 40 billion, behind the U.S., UK, and France. As for aid, a recent McKinsey report put China in third place, with the U.S. once more leading the pack.

When it comes to infrastructure financing, however, the Asian giant is head and shoulders above the rest, with funding worth USD 21 billion in 2015. By contrast, France—China’s nearest rival—stumped up a paltry USD 3 billion. And China is far and away Africa’s largest trading partner—despite a marked decline in African exports to China in recent years on low commodity prices.

Examining longer-term trends is even more illuminating. Between 2011 and 2016, Chinese FDI in Africa more than doubled—supported by institutions such as the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China—while investment from all other key players stagnated. If this tendency continues, China is set to become the largest investor on the continent within a few years.

A blossoming economic partnership has gone hand-in-hand with a concerted effort by China’s leadership to forge closer political ties with the continent. Between 2007 and 2017, top Chinese officials visited Africa 79 times, while Xi Jinping made a point of choosing the continent for his first foreign tour after being elected leader in 2013—and again after reelection in 2018.

Such gestures have solidified bilateral ties, but China has gone one better. Since 2000, the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) has been held every three years, creating a multilateral platform for China and African nations to work together to foster political and economic relations. The reaction from most African leaders to this charm offensive has been effusive: Cyril Ramaphosa, president of South Africa, claimed that FOCAC initiatives will have a “significant and lasting impact on peace, stability and sustainable development on the African continent”, while Paul Kagame, president of Rwanda, declared that China views the continent “as an equal”, and that this is a “revolutionary posture in world affairs”.

China’s eager engagement contrasts starkly to the aloof attitude of most other key players. The U.S. has retreated from the continent under Donald Trump’s leadership; the president has yet to visit Africa, while his plans to cut foreign aid will do little to endear himself to African leaders. British Prime Minister Theresa May did pay Africa a visit in 2018—but it was the first such trip in five years by an incumbent British prime minister. Only France’s Emmanuel Macron, who has travelled to Africa on numerous occasions since being elected last year, has shown an interest comparable to China’s.

The Economic Upshot

Greater Chinese involvement has in many ways been a boon for African economies. According to research by McKinsey, there are around 10,000 Chinese firms operating on the continent today, providing jobs for several million Africans. Rather than being purely extractive in nature, these companies are in it for the long haul; the majority offer training programs for local workers, introduce new products, services and know-how to African markets, and generate tens of billions of dollars in taxable revenue.

Getting products and services to market has been another key theme of Chinese investment. The Asian giant has driven a major overhaul of Africa’s crumbling infrastructure, through financing which often compares favorably in terms of interest rates and repayment schedules to that offered by Western institutions.

The impact throughout Africa has been uneven. According to John Ashbourne, senior emerging markets economist at Capital Economics, “The places where China’s engagement has had the most effect tend to be economies that were shunned by Western investors in the 1990s and 2000s. Chinese firms invest across the continent, but in Angola, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia and other places with a less established Western presence, the Chinese have become the dominant players.”

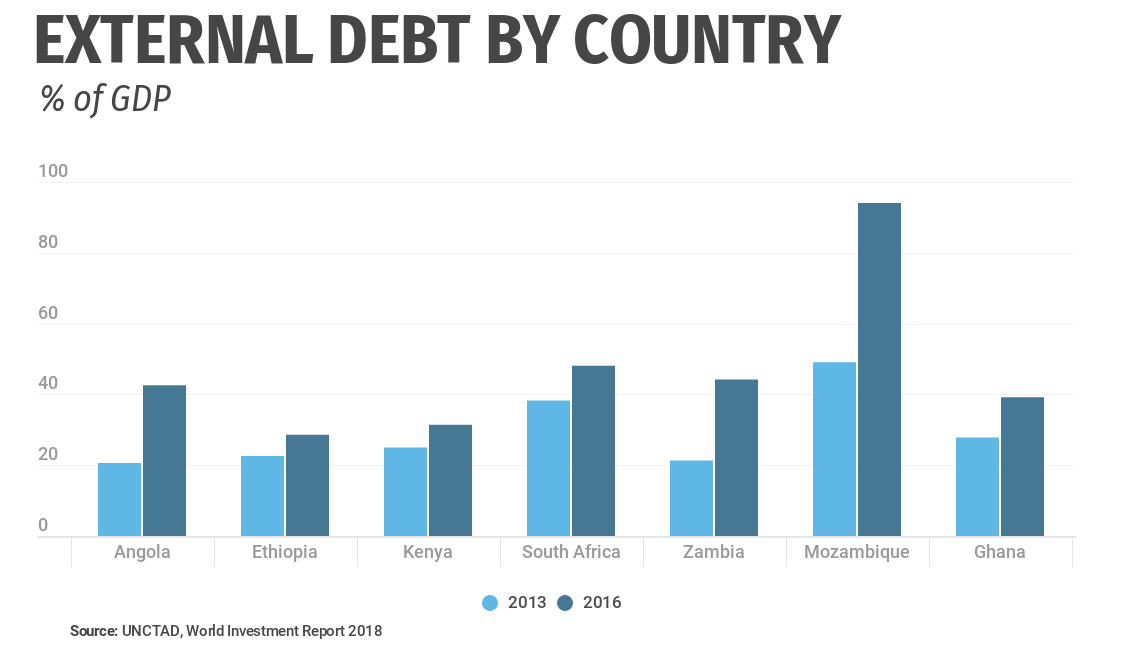

China’s influence has brought problems, too. As Chinese loans to Africa have risen, so have many African countries’ public and external debt burdens in tandem. In Djibouti for instance, where Chinese funding accounts for around 75% of GDP, the public debt ratio nearly doubled in the 2014–2016 period.

This could hamper African countries’ ability to spend on growth-enhancing areas and stokes fears of a loss of economic sovereignty as well as concerns over China repossessing state assets if governments are unable to cough up the cash—as occurred with a Sri Lankan port late last year. Debt repayments could be made harder by the fact that some Chinese investment projects are hard to justify economically—and time will tell whether the Nairobi-Mombasa railway should be placed in this category.

Faced with budgetary pressures, countries such as Ethiopia and Zambia have attempted to restructure their debts, while Zambia has sought assistance from the IMF. According to William Atwell, practice leader for Sub Saharan-Africa at Frontier Strategy Group (FSG), an economic forecasting firm, “40% of economies in the region are in debt distress or at high risk, including Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Zambia, Angola and Ghana”.

However, fears of governments being forced to hand over the keys of strategic infrastructure to China seem overblown; on the whole, the Asian giant has so far been a fairly lenient paymaster, showing a willingness to rework loans and extend repayment periods.

Moreover, Mr Atwell argues that the link between greater Chinese financing and rising African debt burdens should be put into perspective: “China is not the sole source of Africa’s growing debt problem. Economies are accumulating – in some cases unmanageable – new debts from several sources, including concessional and commercial loans from Western institutions, and Eurobonds issued on international markets”.

A Maturing Relationship

China has recently moved to address concerns that heavy lending to some African governments allows it to wield undue political leverage. At the most recent FOCAC conference in September this year, in front of a sea of African leaders, Chinese President Xi Jinping set out his “five no’s” strategy: promising not to alter developmental paths, interfere in African countries’ affairs, impose China’s will, attach strings to financial assistance, or seek political gain.

The Chinese premier also announced debt relief measures and signaled a more cautious approach to lending, amid swirling trade tensions with the U.S. and a flagging domestic economy. The USD 60 billion pledged at the conference merely matched the previous summit’s figure.

African countries themselves must also take responsibility for ensuring they extract the maximum benefit from tighter Sino-African relations. Institutionally, the continent is still one large alphabet soup, with numerous overlapping trade blocs and political groupings. Negotiating en-masse would give Africa greater clout and secure more favorable financing conditions.

In this sense, the agreement between 44 nations earlier this year to establish the African Continental Free Trade Area is an encouraging development—even though regional heavyweights Nigeria and South Africa sat on the sidelines.

African leaders should be more judicious about which projects to throw their weight—and public cash—behind, carry out rigorous cost-benefit analyses and carefully monitor the build-up of debt. They should also push for greater technological transfers to speed up Africa’s industrialization. At present, the continent still largely exports primary goods to China, and imports manufactured products.

Sino-African relations are far from perfect. But in a continent which has for decades lagged behind the rest of the world in terms of economic development, China’s growing influence has been largely positive, leading to an important injection of cash and expertise and opening the door to China’s colossal domestic market.

As for charges of neo-colonialism, John Ashbourne is dismissive: “China’s influence is nothing like the old forms of colonialism. Indeed, Chinese political and military influence is still far less than what France exerts over its former colonies – where it often has military bases, strong trade ties, and long-standing political relationships. It’s true that Beijing is now an influential player in Africa, but […] calling its actions there ‘colonial’ would stretch the word too far.”