“When I was growing up, pizzas and burgers didn’t exist, everything was made at home,” says Carmen as she bustles around the kitchen. “I used to help my mum prepare meals. Now, people don’t have time to cook, so they eat more frozen and processed food.”

Spain may still be renowned as a standard-bearer of the Mediterranean diet based on olive oil, vegetables and fresh seafood, but eating habits have changed beyond recognition here since democracy was restored roughly 40 years ago. Where once stood small stores selling lentils, beans and chickpeas by the kilo, are now the fast-food joints visible in any other capital city. Young people are increasingly rejecting the culinary techniques and habits of their elders.

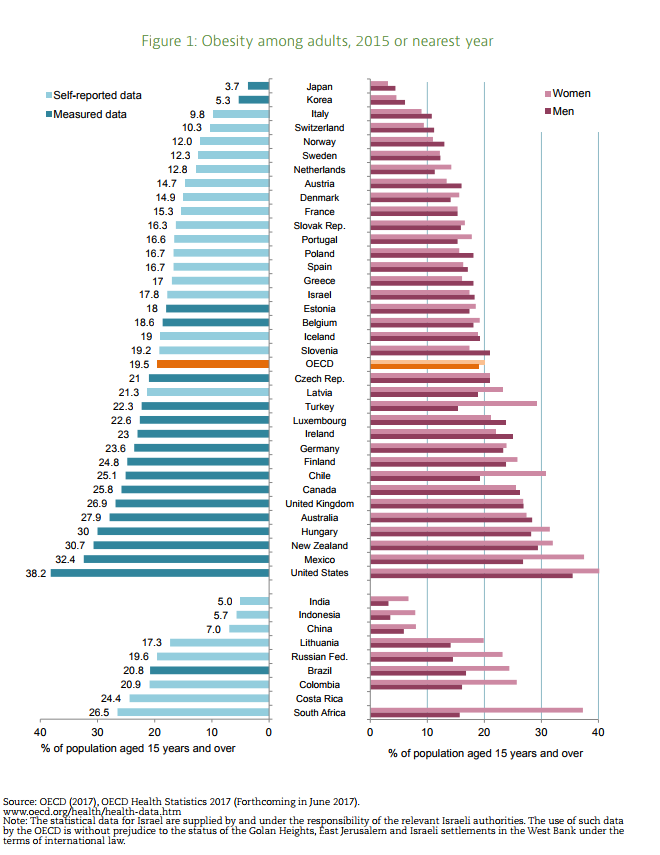

In 2015, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), a branch of the UN, published a report highlighting how the Mediterranean diet, which has long been associated with healthy living, is slowly disappearing. This, coupled with a rise in sedentarism, has led the obesity rate in Spain to rise from less than 10% in the early 1990s to 16.7% according to the most recent data. For broader cross-country snapshots—and how health trends feed into growth assumptions—visit our Consensus Forecast.

This is far from an isolated trend. Obesity rates have shot up across the developed world in recent decades. Within the EU, they are the highest in England, Hungary and Finland. The worst offender among advanced nations is the U.S., where well over a third of adults were classified as obese in 2015. Startlingly, there are now more than twice as many overweight and obese people worldwide as there are undernourished people.

And this swift rise shows no signs of stopping. The OECD expects obesity rates to increase almost inexorably across nations in the years ahead, closing in on 50% in the U.S. by 2030. No developed country has yet cracked the code of dealing with this visible, yet ever-more pervasive global epidemic.

Obesity has long stopped being a first-world problem, however. Many low- and middle-income nations are getting fat before they get rich. They suffer from the coexistence of undernutrition and obesity, the so-called “double burden of malnutrition”. Obesity rates are increasing 30% faster in low- and middle-income nations than in rich ones. Mexico, for example, has a higher obesity rate than all OECD countries bar the U.S.

The WHO describes the situation in grim tones. The agency warns that obesity is “taking over many parts of the world”, and “threatens to overwhelm” countries’ capacities to cope. The economic impact of this dramatic physiological change is making itself felt. Healthcare systems, already buckling under the strain of having to treat ageing populations, are being hit hard.

The direct medical costs due to the greater prevalence of health problems exacerbated by obesity such as diabetes, strokes and hypertension can be significant. For instance, according to the British government in the UK more is spent each year on the treatment of obesity and diabetes than on the police, fire service and judicial system combined.

But direct medical costs are often dwarfed by the indirect costs. Research has shown that obese people are less productive than those with a healthy weight, take more sick days and work fewer hours. They are also more likely to be unemployed, earn less and claim disability payments. After taking these factors into account, the UK government estimates that the total cost to the economy of people being overweight and obese was GBP 27 billion in 2015. Within a few decades, it is forecast to hit GBP 50 billion.

Less discussed are the negative environmental externalities. Excessive calorie consumption leads to greater food production. This has an impact on greenhouse gas emissions, with a greater number of methane-producing livestock, more oil-hungry plastic packaging and higher demand for transport in order to get goods onto supermarket shelves.

Transporting heavier passengers also requires more fuel. One study by the OECD suggested that an average reduction in weight of 5 kg across nations could stop 10 million tons of CO2 a year from being released into the atmosphere. Putting precise figures on the economic cost of all these environmental spillovers is notoriously tricky, but they undoubtedly run well into the billions.

Within nations, rising obesity threatens to deepen the social divides which have become ever starker in recent decades due to sweeping technological change. Rebecca Williams, Public Health Consultant in England’s National Health Service says, “There is a strong relationship between obesity and low socioeconomic status and in Europe, adults from low socioeconomic groups are twice as likely to become obese as those from higher groups.” By damaging labor market outcomes, obesity will only entrench economic inequality further.

With the devastating economic consequences of obesity ever more apparent, governments across the globe are slowly stirring, and the tide of opinion is gradually turning in favor of fiscal incentives. In the EU, Hungary is leading the charge. A comprehensive tax on foods high in salt, fat and sugar has been in place since 2011, with the funds raised reinvested in the national health service. Early signs are encouraging; two years after being introduced, 30% of Hungarians reported changes to their consumption patterns.

Other countries are following suit. In Spain, the regional government of Catalonia introduced a tax on sugary drinks in May this year. The UK, Ireland and Estonia are on course to implement a similar tax in 2018. Taxes on junk food have long been favored by economists as a way of making consumers pay the full social cost of their consumption. In practice, however, choosing exactly which foodstuffs should be taxed is tricky, and critics argue the tax is regressive, as the poor tend to spend a higher proportion of their income on unhealthy food than the rich.

Faced with the more proactive stance of governments, the food and drink industry is fighting tooth and nail to preserve the juicy profit margins generated from junk food. According to the Corporate Europe Observatory (CEE), a research group which aims to expose the power wielded by corporations in the EU, “over the past decade the food industry has vigorously mobilised to stop vital public health legislation [regarding excess sugar consumption]”.

The CEE claims food companies spent EUR 21.3 billion annually to lobby the EU. The success of this lobbying was evident in 2014, the organization argues, with Denmark’s decision to overturn a decades-old sugar tax.

The food and drink industry was likely cheering in late September, when the EU scrapped quotas on sugar production. Health experts warn this could lead to a flood of cheap sugar on the market, potentially undoing overnight years of hard work to try to rein in consumption.

Whatever the eventual impact of junk food taxes, Rebecca Williams makes it clear that this is only one of the myriad policy initiatives required to reduce obesity, improve health outcomes and limit economic damage. “Addressing the many factors that contribute to an obesogenic environment needs comprehensive cross-cutting action across all areas of the system—focusing on just one factor in the system is very unlikely to be successful.”

“Action is needed in areas such as altering the composition of foods, reducing traffic congestion, improving transport infrastructure and urban design, encouraging cycling and walking, reducing crime, making it easier and cheaper to buy healthy foods, teaching cooking skills and encouraging cultural changes in values around food and activity.”

When asked whether she thinks the sugar tax recently introduced in Catalonia will help reduce obesity levels, Carmen Cano replies, “It’s a first step, and companies are now offering drinks with less sugar.” Then she continues, “But prevention is key, and there are still no awareness campaigns in schools. Much more needs to be done.”

Photo Credit: “fast food is the best!” by ebruli is licensed under CC BY 2.0