Major Geopolitical Events and Their Effect on Oil Prices

For decades, the price of crude oil has been a sensitive barometer of global stability. More than just a commodity, its cost is a fever chart of geopolitical health, spiking with conflicts and crashing with unforeseen calamities. To understand the ebb and flow of the world’s most critical energy source is to read a history of modern crises. From Arab-Israeli tensions to a global pandemic, major events have consistently demonstrated their power to convulse the oil market, reshaping economies and international relations in the process.

The Oil Crisis of the 1970s: A Rude Awakening

The 1970s shattered the post-WW2 illusion of cheap and abundant energy. The decade was punctuated by two major oil shocks that fundamentally reconfigured the global economic landscape. The first, in 1973, was a direct consequence of the Yom Kippur War. In response to American support for Israel, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) imposed an embargo on the United States and other nations. This was not merely a commercial dispute; it was the weaponization of oil.

The effect was immediate and dramatic. The price of oil per barrel quadrupled, soaring from around USD 3 to nearly USD 12 by the time the embargo was lifted in March 1974. For a world built on cheap oil, the shock was profound. The United States, where domestic production had peaked in 1970, was particularly vulnerable, having become increasingly reliant on imports. The iconic images of the era are of long queues of cars snaking around petrol stations, a visceral symbol of a new era of energy scarcity.

The second shock of the decade arrived with the Iranian Revolution in 1979. The overthrow of the Shah and the ensuing chaos crippled Iran’s oil industry, removing millions of barrels from the daily global supply. The subsequent Iran-Iraq War further decimated the production of both nations. While other OPEC members increased their output to compensate, it was not enough to prevent another price surge. By 1980, oil prices had more than doubled again, reaching over USD 36 per barrel, a fourteen-fold increase from the start of the 1970s. The decade served as a harsh lesson in the strategic importance of oil and the immense power wielded by those who control its flow.

The Gulf War (1990–1991): A Swift, Sharp Shock

The summer of 1990 brought another stark reminder of the Middle East’s critical role in energy security. Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in August immediately threatened a significant portion of the world’s oil supply. Iraq and Kuwait together accounted for a substantial slice of OPEC’s output. The invasion, motivated by Iraq’s heavy debts from the Iran-Iraq war and its accusation that Kuwait was overproducing and depressing prices, sent a jolt through the market.

Oil prices reacted with predictable alarm. The average monthly price of a barrel shot up from USD 17 in July to USD 36 by October. The fear was not just the loss of Iraqi and Kuwaiti oil, but the potential for the conflict to spill over into neighboring Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest oil exporter. The United Nations responded by imposing an embargo on Iraqi and Kuwaiti oil, further tightening supply.

However, the 1990 price shock proved to be less severe and of shorter duration than those of the 1970s. The swift and decisive military intervention by a U.S.-led coalition to oust Iraqi forces from Kuwait calmed market fears of a prolonged supply disruption. As the coalition’s military success became apparent, prices began to fall. The episode demonstrated that while the market remained highly sensitive to geopolitical ructions in the Gulf, a rapid and effective international response could mitigate the economic fallout.

The 9/11 Attacks: A Demand-Side Shock

The terrorist attacks of September 11 2001 were a tragedy that shook the world. Their impact on the oil market, however, was different from previous crises. Rather than a supply shock, 9/11 triggered a sudden and severe demand-side shock. The immediate aftermath saw the world’s aviation industry grind to a halt. The grounding of aircraft and the subsequent deep aversion to air travel led to a collapse in the demand for jet fuel, a key component of oil consumption.

This precipitous drop in demand sent oil prices tumbling. The attacks created a climate of profound economic uncertainty, further dampening consumer and business confidence and, consequently, energy consumption. While the price drop was significant, it was relatively short-lived as the global economy gradually found its footing. The 9/11 attacks highlighted a different kind of vulnerability for the oil market: Its deep integration with the rhythms of the global economy and the sudden impact that a non-energy-related catastrophe could have on demand.

The Global Financial Crisis: A Cascade of Collapsing Demand

The financial contagion that began in the American subprime mortgage market in 2007 and erupted into a full-blown global crisis in 2008 delivered the most significant demand-driven oil price shock in modern history. In the first half of 2008, oil prices had surged to unprecedented highs, peaking at over USD 147 a barrel in July. This was driven by a combination of robust demand, particularly from emerging economies like China, and stagnant production.

Then, the bottom fell out of the market. As the financial crisis crippled the world’s leading economies, industrial activity seized up and commerce slowed dramatically. Demand for energy plummeted. As a result, oil prices went into a freefall, collapsing to a low of USD 32 a barrel by December 2008. This represented a staggering 80% drop in just a few months. The crisis demonstrated with brutal clarity how intertwined the fate of the oil market is with global economic health. No amount of supply-side discipline from OPEC could counteract a demand shock of this magnitude.

The Iranian Nuclear Deal: A Glimmer of New Supply

For years, Iran’s vast oil reserves were largely kept off the mainstream market by stringent international sanctions aimed at curbing its nuclear program. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), agreed upon in 2015 between Iran and several world powers, offered the prospect of a significant change in the global oil supply picture. The deal involved the easing of sanctions in return for limitations on Iran’s nuclear activities.

The prospect of a new influx of Iranian oil had a tangible effect on prices. Even before the deal was finalized, prices dipped on the expectation of sanctions being lifted. When the agreement was implemented in January 2016, Iran was able to increase its oil exports, which had been slashed by the sanctions. This contributed to a global supply glut that helped keep prices relatively low. However, the full potential of Iranian production was never realized due to lingering political risks and the eventual withdrawal of the United States from the deal in 2018, which led to the reimposition of sanctions. The episode illustrated how diplomatic breakthroughs, as much as conflicts, can recalibrate oil market dynamics.

The Covid-19 Pandemic: A Black Swan Event

The Covid-19 pandemic was a geopolitical event of a different order, a global health crisis that triggered an economic shutdown of unprecedented scale. The impact on the oil market was catastrophic and, at one point, surreal. As nations went into lockdown and travel was banned, demand for oil evaporated. Global oil demand crashed by a record amount in 2020. This demand shock was compounded by a simultaneous price war between Russia and Saudi Arabia, which flooded the market with crude. The result was a spectacular collapse in oil prices. In April 2020, for the first time in history, the price of West Texas Intermediate (WTI), the U.S. benchmark, fell into negative territory, dropping to around minus USD 38 a barrel. This meant that producers were literally paying buyers to take their oil, as storage facilities were overwhelmed. The pandemic laid bare the oil industry’s vulnerability to “black swan” events that can obliterate demand in a way that no one could have foreseen.

The War in Ukraine: The Return of the Geopolitical Risk Premium

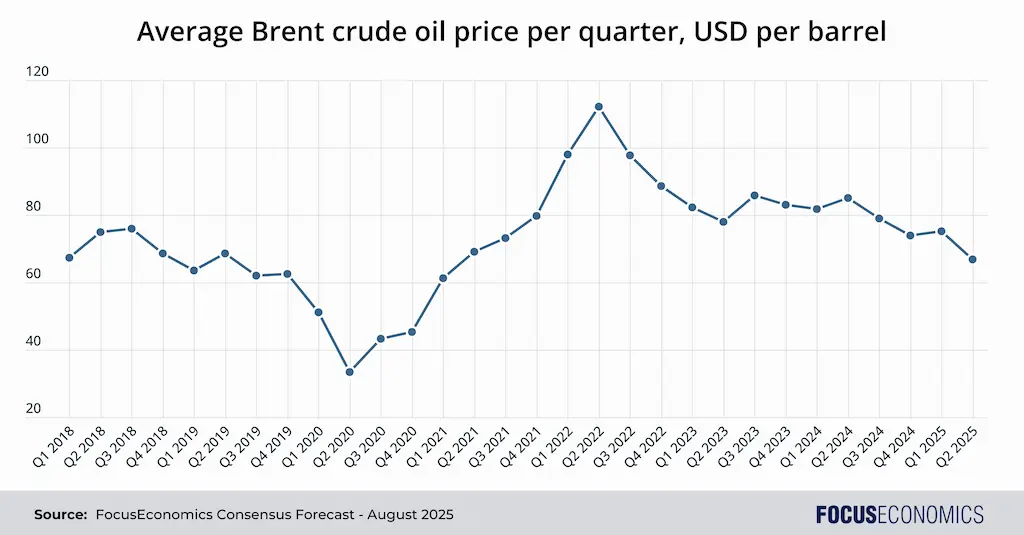

The invasion of Ukraine by Russia in February 2022 brought the issue of energy security roaring back to the forefront of the global agenda. The conflict triggered a dramatic spike in oil prices, which surged to over USD 110 a barrel. Russia is the world’s third-largest oil producer and the prospect of its supplies being cut off from the global market due to sanctions sent shockwaves through the system. While the global oil market has since adjusted, with Russian oil finding new buyers in Asia, the war temporarily reintroduced a significant geopolitical risk premium into the price of oil.

Current Market Conditions

On the supply side, the OPEC+ grouping of oil-producing nations has been ramping up output since April following several years of strict output curbs. Production from key non-OPEC+ producers such as Iran and Venezuela has been fairly stable in recent months despite the U.S. administration adopting a tough diplomatic stance towards both nations. The ramp-up of OPEC+ supply, coupled with demand concerns due to higher global tariffs, has caused both Brent and WTI crude prices to slump to below USD 70 per barrel for much of the year to date.

Comparing Brent Crude and WTI Price Movements

Think of Brent and WTI crude as two different, but related, stocks in the energy sector. Brent, from the North Sea, is the global benchmark, reflecting international supply, demand and geopolitical risk. WTI is the U.S. benchmark, priced in landlocked Oklahoma.

While their prices generally move in tandem, the gap between them—the “spread”—is what matters. Historically, WTI was pricier, but the U.S. shale boom reversed this, creating an oversupply in the States and widening the spread as transport out was limited.

Today, Brent typically trades at a premium. This spread fluctuates based on U.S. production levels, pipeline capacity, American demand and global events affecting seaborne oil. A wide spread signals U.S. market dislocations, while a narrow spread suggests a more balanced global market; watching this gap offers a quick read on the relative health of the U.S. versus the international oil scene.

Our Panelists’ Forecasts

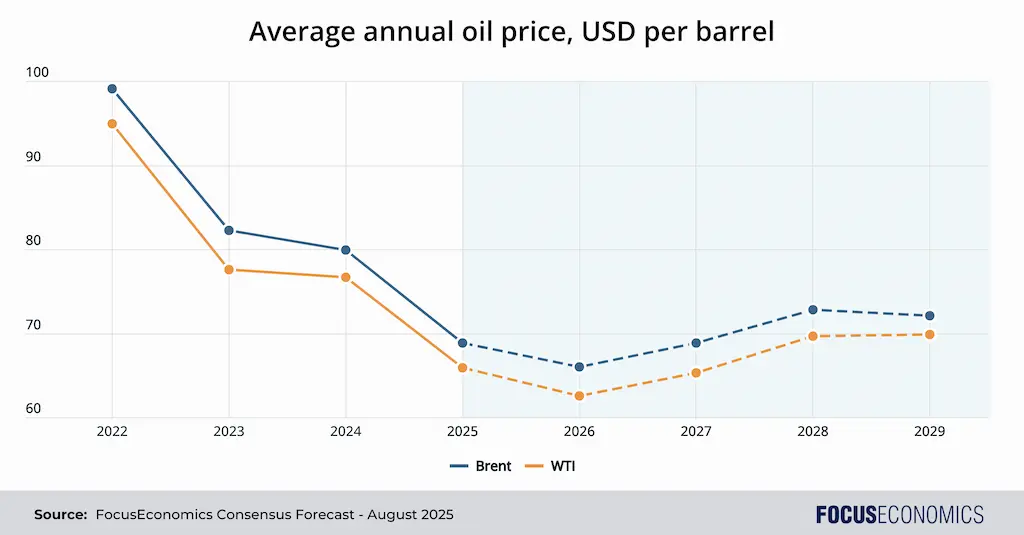

The Consensus among the 43 expert analysts that make up our panel is for the price of oil to tick up slightly in the coming years, with the average 2029 price for Brent forecast around 5% above the 2025 price. Moreover, Brent’s positive spread to WTI is seen persisting in the coming years, albeit only slightly.

However, Brent crude prices are projected to remain far below the inflation-adjusted 30-year average of USD 83 per barrel. The global transition towards cleaner energy sources—though likely to slow due to the fossil-fuel-loving U.S. president—will cap future oil demand.

As EIU analysts said:

“Oil demand will hit record highs in 2025 and 2026 (and beyond), but average annual growth will decelerate significantly from the recent trend to 0.6% per year throughout the forecast period (2025-29), or the equivalent of about 650,000 barrels/day in 2025 and 2026. We do not expect global consumption to peak until 2034. North America will remain an exception to the trend of secular decline in the developed world throughout the second Trump presidency. […] With policymakers in China prioritising EV and electrification targets, India will increasingly become a driver of non-OECD growth, especially towards the end of the decade.”

Conclusion: Navigating the Future of the Oil Market

From the deserts of the Middle East to the halls of international diplomacy and the unforeseen devastation of a global pandemic, major world events have consistently left their indelible mark on the price of oil.

This will remain the case going forward. For instance, potential U.S. sanctions relief for Iran is a downside risk to the market, as it would likely involve a loosening of U.S. restrictions on Iranian oil. On the flipside, further Iran-Israel conflict that disrupts oil flows is an upside risk. U.S. tariff policy, U.S.-China frictions over Taiwan, sanctions on Venezuelan oil and OPEC+ quota changes are further geopolitical factors that will shape the outlook.