Historical Trade Relations between the U.S., Canada and Mexico

The trade relationship between the United States, Canada and Mexico is one of the world’s most intricate economic tapestries, woven from threads of shared geography, resource complementarities, and, crucially, evolving political will. From colonial-era bartering to the sophisticated supply chains of the 21st century, this trilateral dynamic has shaped not only North America’s prosperity but also global trade patterns.

The earliest trade between the territories now known as the U.S., Canada, and Mexico was dictated by natural endowments and the needs of colonial powers. Canada, rich in furs and timber, found an early market in the burgeoning American colonies, which in turn supplied agricultural products and manufactured goods. Mexico, with its vast silver mines and unique agricultural outputs like cochineal, traded both northwards and across the Atlantic.

The 19th century saw these relationships formalize and, at times, fracture. The Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 between British North America (Canada) and the U.S. marked a significant, if temporary, lurch towards free trade, eliminating customs duties on a wide range of natural products. Its abrogation by the U.S. in 1866, amid post-Civil War tensions and protectionist sentiment, spurred Canada towards its own National Policy in 1879, a system of tariffs designed to foster domestic industry. Despite this, cross-border trade continued, driven by geographical proximity and the development of rail networks.

With Mexico, the 19th century was more tumultuous. Following its independence and the Mexican-American War, trade was often overshadowed by political instability and U.S. expansionism. However, the Porfiriato era (late 19th–early 20th century) saw the U.S. invest significantly in Mexican railways and mining, in turn fostering closer economic ties—albeit on unequal terms.

Following decades of protectionism and the global devastation wreaked by World War II, the latter half of the 20th century brought a shift towards greater regional economic integration, initially between Canada and the U.S., and later with Mexico.

For additional context and regularly updated projections, see our Consensus Forecast.

The Evolution of Trade Agreements Between the U.S., Canada and Mexico

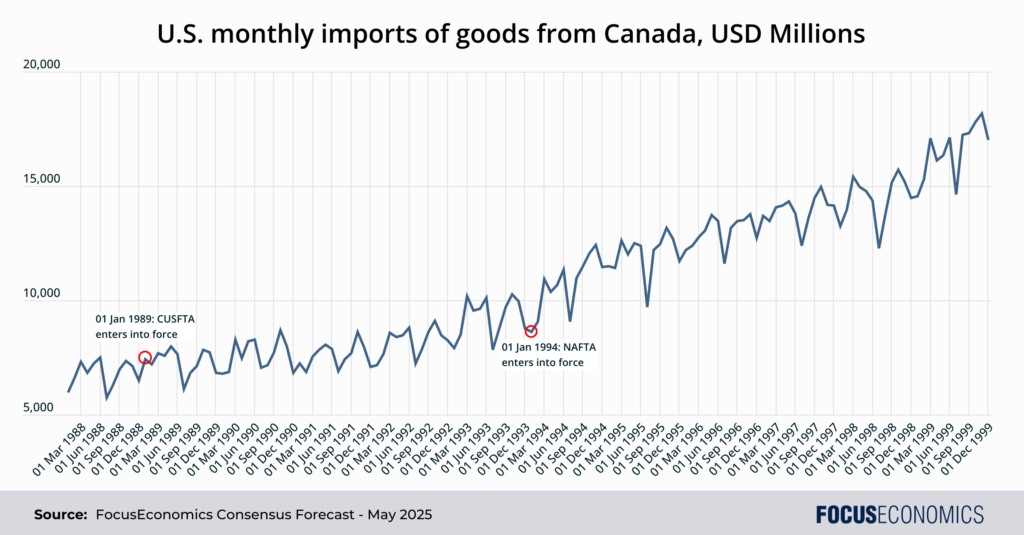

The late 1980s witnessed the first major modern step towards a North American economic bloc in the form of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (CUSFTA), which came into effect on 1 January 1989. CUSFTA was groundbreaking: It aimed to eliminate all tariffs on bilateral trade over a ten-year period, liberalize investment, and, crucially, establish a novel binational dispute settlement mechanism.

The ink on CUSFTA was barely dry when a more ambitious vision emerged. Mexico, under President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, was undergoing a radical economic liberalization. Salinas saw a free trade agreement with the U.S. (and by extension, Canada) as a way to lock in these reforms, attract foreign investment and boost export-led growth. The outcome was the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), a comprehensive, North America-wide free trade deal that supercharged trilateral commerce.

Not everyone was happy though; in particular, U.S. critics pointed to manufacturing job losses, a widening trade imbalance and downward pressure on wages. This culminated in a U.S.-led push to renegotiate some aspects of the deal under Donald Trump’s first presidency, with NAFTA subsequently relabeled as USMCA to reflect these changes; USMCA came into force in 2020.

The U.S. Tariffs Recently Levied Against Canada and Mexico

Unsatisfied with the renegotiation he himself championed, in early 2025 Donald Trump imposed a range of tariff measures affecting Canada and Mexico. First came direct tariffs of 25% against most non-USMCA-compliant goods from both countries, followed by specific 25% tariffs on cars, steel and aluminium.

Canada and Mexico’s Response to U.S. Actions

Canada responded swiftly, imposing import taxes of 25% on about USD 43 billion of U.S.-made goods in March in response to the first round of tariffs from Trump. That said, subsequent exemptions have reportedly reduced the effective tariff rate to near-zero. Meanwhile, Mexico’s government took a more measured approach, avoiding any retaliatory tariffs and instead opting for dialogue. Given that Canada and Mexico rely heavily on the U.S. market—both countries send close to 80% of their goods exports to the U.S.—the Trump administration has the upper hand in talks.

Can The Tariffs Be Dodged?

Yes—but not entirely. Many goods that do not currently enter the U.S. under the USMCA likely could do so if firms opt to fill out the extra paperwork—which they now have a clear incentive to do. That said, a minority of firms would have difficulty meeting rules of origin requirements in order to qualify for USMCA, chiefly firms that source a high share of their inputs from outside North America. This could lead some businesses to stretch rules of origin definitions to the limit, shifting finishing processes across borders to claim preferential status.

BBVA analysts commented on the potential to make Mexican goods USMCA-compliant:

“Many exporters who previously avoided using the USMCA due to the administrative costs of demonstrating compliance with rules of origin may be reevaluating their decision in light of the new tariff environment. Although it is impossible to determine precisely how many companies will adopt the agreement, more intensive use is anticipated. In the automotive sector, the US content of exports is expected to be systematically documented in the short term, allowing for tariff deductions and significantly reducing the tax burden.”

Another option could be to reroute goods via third countries, though given the 10% baseline tariff currently in place on the rest of the world and the threat of higher “reciprocal” tariffs to come, the incentive for firms to make such a move could be limited. Underreporting the value of goods heading to the U.S. or mislabeling goods so they appear to qualify for the tariff exemption are additional steps that companies may take.

Lobbying hard for exemptions and the rollback of tariffs—both by North American firms and governments—will continue. Trump has already shown his willingness to bend, repeatedly backtracking on his more extreme tariff measures when put under political pressure.

On the Canadian government’s efforts to influence Trump under new Prime Minister Mark Carney, EIU analysts said:

“Mr Carney’s next move on trade is likely to be to attempt to initiate senior-level discussions with the Trump administration, potentially with the US Treasury secretary and current lead trade official, Scott Bessent, in the hope of working towards some partial tariff relief and laying the groundwork for USMCA talks. Our expectation remains that tariffs on Canada will remain high for at least the next two quarters, although some exemptions will be granted for certain sectors (as was the case for autos on April 29th).”

Future U.S. Tariffs on Canada and Mexico

There may be more to come. The U.S. Commerce Department is currently reviewing potential tariffs on electronics, critical minerals, copper and timber. Moreover, the Trump administration is eager to clamp down on the rerouting of Chinese exports via third countries; evidence suggests that Mexico has been an important backdoor for Chinese exports entering the U.S. recently. Given Trump’s unpredictability, there is also the possibility for more levies than those already floated, either sector-specific or deliberately targeting the U.S.’ North American neighbors.

On tariff circumvention, Nomura economists said:

“Mexico and Vietnam are likely behind China’s hidden trade with the US […]. After adjusting for circumvention through third countries in Southeast Asia and Mexico, Nomura’s China economics team estimates that China’s direct and indirect exports to the US comprised 18.5% of its total exports in 2023, down from 20.6% in 2017, but not as low as the direct export share fall would suggest.”

On the flipside, successful negotiations between the three North American nations—presumably involving some concessions to Trump to boost U.S. industry, to curb migration and drug trafficking, to reduce imports and to shut out China—are also a possibility; such an outcome could see tariffs fall from current levels. In short, a multiplicity of outcomes is on the table.

Impact on the Outlook for Canada and Mexico

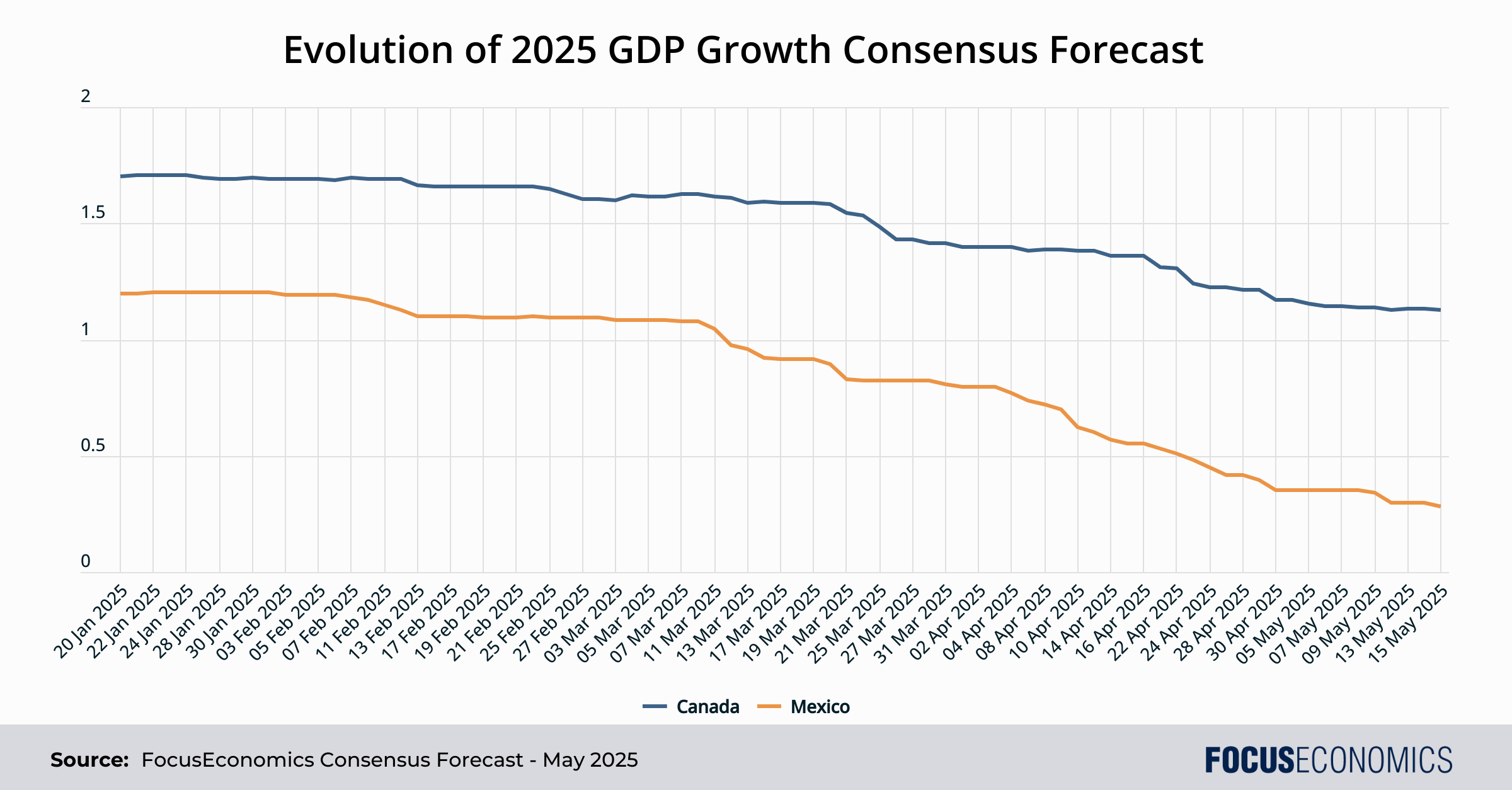

Our panelists have slashed their forecasts for both Canadian and Mexican 2025 economic growth since Trump’s inauguration in January. Mexico has seen the larger downward revision to the Consensus Forecast, of 0.9 percentage points, with Mexico’s GDP now expected to grow a measly 0.3% this year. Forecasts for Canada’s GDP have been downgraded by 0.6 percentage points, though the economy is still expected to grow slightly above 1%.

The heavier downgrade for Mexico likely reflects the country’s more limited room for fiscal stimulus vs Canada, plus the fact that Mexico exports more cars and Canada more energy; U.S. tariffs on Canadian energy are currently lower than tariffs on cars. In addition, Mexico’s economy could be hit by reduced remittances due to the U.S.’ crackdown on migration, whereas remittances aren’t a relevant contributor to Canada’s economy.

One possible upside could emerge if the U.S. follows through with much higher “reciprocal” tariffs on the rest of the world. Such tariffs are currently paused until July, but if brought into effect, they would make producing in Canada and Mexico relatively more attractive, even if both countries are still subject to levies themselves.

As BBVA analysts say:

“A plausible scenario [for Mexico] considers deducting US content (an average of 18.3%) in automotive exports, reducing the average tariff to 13.1%. If, in addition, the share of exports under USMCA rises to its historical peak (64.2%), the tariff could drop further. Moreover, if the Trump administration agrees to cut migration—and fentanyl-related tariffs to 12%, the average could fall to 8.4%. This would place Mexico among the countries with the lowest levels of relative protectionism from the US worldwide.”

Long-term Economic Impact

The long-term effect of U.S. tariffs on Mexico and Canada will hinge on whether they turn out to be a temporary blip or the beginning of a broader trade unraveling—and also on what tariffs are levied on the rest of the world. Though U.S. policy is extremely volatile at present, Donald Trump’s decision to exclude Canada and Mexico from the list of “reciprocal” tariffs suggests he recognizes some value in North American trade, at least for now.

Next year—when the USMCA comes up for renewal—should provide more clarity on the long-term future of the deal; until then, related uncertainty may paralyze manufacturing investment in Canada and Mexico. However, even if USMCA survives, it will likely only do so in a modified form aimed at reducing the U.S. trade deficit.

On the chilling effect of uncertainty on investment, EIU analysts said:

“We are doubtful of any immediate breakthroughs in US talks with trading partners, including over the future of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). This means that US tariffs will probably remain elevated for the foreseeable future, and additional sectoral tariffs may be applied on important segments of Mexico’s exports, such as consumer electronics and appliances. A lack of clarity on the application of current tariffs, including confusing and constantly changing auto levies, and uncertainty about the future of US trade policy will continue to dent private investment.”

The Bottom Line

Despite all the uncertainty, it seems safe to assume one thing: Canada and Mexico will face higher U.S. trade barriers in the next four years than they have previously. This will knock economic growth in both countries, despite possible trade diversion from Asia and Europe. As politicians of many stripes have repeated tirelessly in recent months, no country wins in a trade war.